#gia kourlas

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Feminism & Ballet

Gia Kourlas has an excellent opinion piece in the New York Times on Balanchine and the culture of ballet.

CRITIC’S NOTEBOOK Finding Freedom and Feminism in Ballet (It’s Possible)

With new books and a podcast taking another look at the legacy of George Balanchine and the culture of ballet, where does a modern ballerina stand?

By Gia Kourlas April 5, 2023

Ballet requires—no, demands—devotion. But what is the price of that devotion, especially for women? Ballet these days is under fire in some quarters, and the very idea of devotion to it has become suspect. A myth has grown around it: that its price is physical and mental abuse, eating disorders, bloody toes, suffering, pain and blind subservience to patriarchal leaders.

And it’s not just ballet, but George Balanchine’s vision of ballet, which seems to be, again, causing controversy as familiar stereotypes are revived, including the idea that he preferred extremely thin dancers with tiny heads and long legs.

With the recent release of a biography about Balanchine, a memoir by a former ballet student who failed to advance at the School of American Ballet―which Balanchine co-founded, along with New York City Ballet—and a podcast anchored on Balanchine, the choreographer and his legacy are floating in the air.

Balanchine demonstrating in class at the School of American Ballet, 1960. Photo: Nancy Lasalle via Eakins Press/George Balanchine Trust/The New Yorker

Balanchine told dancers, “Don’t think, dear, do,” which inspired the title of Alice Robb’s memoir, “Don’t Think, Dear: On Loving and Leaving Ballet”—though she leaves off the most important word, “do.” But what did Balanchine really mean? He wasn’t telling dancers to turn off their brains, he was urging them to dance in the moment. It was meant to quell overthinking, as in, Get out of your head.

A dancer’s mind is just as important as her body; the one guides the other. To dance fully without hesitation, without self-consciousness, sets the stage for dancing of power and flow—to witness such unforced abandon is one of ballet’s greatest gifts. It’s almost as if the mind and body conjoin in a spiritual melding that manifests as a feeling: sensation woven into silken motion. Dancers, in such moments, are celestial beings. Manners and decorum are stripped. It’s not about beauty or grace. The feminist case for ballet is right there onstage: It’s freedom. In his choreography, Balanchine made a space for women in particular—and for each woman—to be free.

Line, proportion, coordination are part of a dancer’s body, but dancing isn’t just about how a body looks. It’s bigger than that. When a dancer is completely in tune with music and steps, something intangible takes over and, as strange as it sounds, the physical body almost disappears. It’s magic, but it isn’t random: after years of training, after hours of repetition, the body becomes a conduit for emotion. Grit meets glory, the body meets the mind. That is Balanchine’s “do.”

Megan Fairchild, second from left, and Joseph Gordon in the first movement of Symphony in C, 2021. Photo: Caitlin Ochs for the NY Times

What is the feminist knock on ballet? That dancers have no agency. That ballet companies are like cults in which women are starved and controlled by men. That gender biases in dance reduce women to objects, especially when it comes to male-female partnering. That, in ballet, women are referred to as girls long after that ship has sailed.

Balanchine these days is seen by some as fostering that culture. In the podcast “The Turning: Room of Mirrors,” Erika Lantz explores the legacy of Balanchine and ballet culture with former company members and writers, who, at times, attack the art form with opinions delivered as received wisdom.

“One of the things that you learn in ballet is what a good woman looks like,” Chloe Angyal, the author of “Turning Pointe: How a New Generation of Dancers Is Saving Ballet From Itself,” says on the podcast. “How you’re supposed to look, how you’re supposed to move, how you’re supposed to behave, how you’re supposed to tolerate pain, how you’re supposed to conceal labor, who you’re supposed to obey, who you get to have power over.

“You learn all that in the ballet studio,” Angyal says. “But the reward for all that is accomplishing this very particular kind of femininity.”

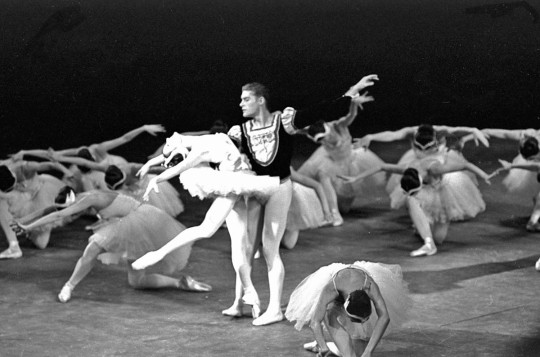

Patricia McBride and Conrad Ludlow in Balanchine's one-act Swan Lake, 1967. Photo: Martha Swope via NYPL

Are all female ballet dancers the same kind of feminine? The dancers that I know are not holding on to a little girl’s definition of femininity; they're independent, strong and, as far as I can tell, they don’t suffer in silence.

And it’s important to remember that Balanchine’s female dancers didn’t all look the same and, even more crucial, that they didn’t all dance the same. What they had—and still do, generations later—was different kinds of femininity, and all of it athletic. Balanchine made ballet faster, sleeker, more daring. But it wasn’t just athleticism alone, it was how that allowed for a more urgent, even wild, expressiveness. He turned dancers into athletes, and athletes into dancers with a mind-body connection so profound that to be able to “do” was not a robotic regurgitation of steps, but a new kind of speaking, of singing with the body. That is still true today—it’s in the choreography.

Kyra Nichols and Charles Askegard in Davidsbundlertanze, 2004. Photo: Paul Kolnik via NYCB

The books and the podcast are focused on Balanchine’s era, which ended with his death in 1983, and into the 1990s. But ballet culture has been going through changes, more quickly than I’ve seen before; companies have become more racially diverse—incrementally, but at least it’s an improvement—and greater attention is being paid to dancers’ well-being. In the past few years, changes have also been made in artistic leadership and accountability. (At City Ballet, Peter Martins retired after accusations of physical and mental abuse; he was later cleared by an independent investigation.) Issues revolving around injury and mental health are taken more seriously; they are no longer sources of shame.

Part of the current reckoning with ballet seems to have much to do with the heartbreak of having to give it up. Midway through “Room of Mirrors,” we learn that Lantz, the podcast’s host, was a ballet student who made the decision to quit. “I don’t know why I’m crying,” she says. “I think it just meant a lot to me at the time. It was like one of the hardest decisions I ever made.”

Robb writes about a similar situation in her memoir, in which she recalls her experience at the School of American Ballet and dips into the biographies of others, including Misty Copeland and Margot Fonteyn. And while there is certainly sadness in Robb’s story, it’s not atypical: at a certain point, she didn’t advance at the school and had to leave; eventually, she quit ballet.

On “Room of Mirrors,” Wilhelmina Frankfurt, a former City Ballet dancer, says: “When you finally do move on, there’s a recovery period. And I think the recovery period into the quote-unquote ‘real world’ takes about 10 years.”

Wilhelmina Frankfurt in the Rubies section of Jewels, 1981. Photo: Steven Caras via stevencaras.com

For many, it is never the right time to leave. That includes students whose bodies can betray them in adolescence and professionals at the top level whose bodies betray them by giving out. Dancers aren’t instruments, but their bodies are their instrument; without the body, the art form doesn’t exist. What other art form relies so entirely on the body?

And there’s something else that tends to be left out of the discussion: ballet is hard. It’s not democratic; while anyone can study ballet (do it!), there is no question that only a rare few progress through years of rigorous training and then join a company. And it’s even more competitive for women—there are so many more of them. But how many Little Leaguers dream about making it to Major League Baseball or young tennis players of winning the U.S. Open?

I’m sensitive to dancers; I see them as people, and while it’s a fine line, I try to be as holistic as possible when writing about them. Musicality and proportion mean more to me than the size of a thigh. Coordination is key—it’s what allows a dancer to move with true abandon. Dancing well, dancing without restraint, is not about a body, it’s what you do with that body.

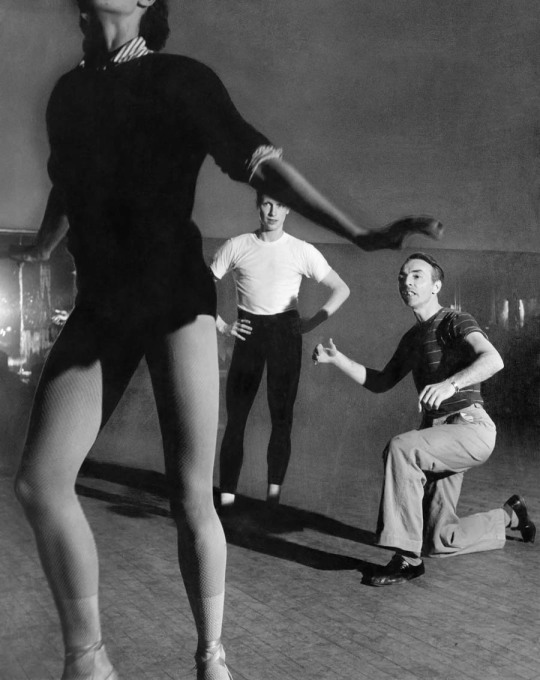

Balanchine working with dancers, 1952. Photo: Sam Falk for the NY Times

When I don’t discuss a dancer’s body—and, no, the idea of line isn’t only a veiled way to talk about weight—it’s a choice. I care most about how the person dances. I don’t fetishize a foot; I care about how the foot moves. I’m also not delusional. Are there physical standards in ballet? Of course. The body, like it or not, is part of the art form, and bodies develop in different ways. Ballet is punishing. There are injuries. It’s not for the weak—of body or mind.

But because it is an art form, ballet exists on another plane, where there is room for mystery and mysticism: So much is said about the silence dancers must maintain, but the body isn’t silent as it seeks harmony with the mind. The freedom in ballet comes when the body is so trained that it relaxes. Again, that’s the do.

The subject of flow came up in a 2022 talk about ballet and basketball with Steve Kerr, the Golden State Warriors head coach, and Alonzo King, the choreographer and artistic director of Lines Ballet in San Francisco. King spoke about dancers who are so absorbed in the moment that “they’re not self-conscious, they’re not thinking about themselves because that prevents the entry,” adding that, “You stop thinking about yourself and then something comes in—it’s that surrender thing that makes openings possible.”

Animating the body to a point in which it surrenders to the moment was part of Balanchine’s magic. He could probably see the potential of dancers more clearly than they could see themselves. But ballet isn’t one-sided. No matter who the choreographer is, it’s the dancer that finds an opening, a dancer that surrenders in real time. It’s a private moment in public, and it requires strength and courage; that’s a kind of feminism. A dancer’s world is neither little-girl pink nor black and white, it’s full of color and nuance and texture. When a dancer is onstage, she is in charge.

Ashley Bouder and Andrew Veyette in the Stars and Stripes pas de deux, 2013. Photo: Paul Kolnik via NYCB

#Balanchine#ballet#feminism#ballet & feminism#dancing#New York City Ballet#NYCB#Gia Kourlas#ballet culture

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Tiny Dancers Who Make ‘The Nutcracker’ Sparkle

The tree, George Balanchine knew, was not going to be cheap. But when he created his version of “The Nutcracker” for New York City Ballet in 1954, he fought for it, saying the ballet “is the tree.”

Watching the tree grow, even with its creaks and trembles — will it make it this time? — is an emotional experience. The tree produces feelings! But “George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker” is also about something else: the children of the School of American Ballet.

If last year’s production proved anything, it was that size and spirit matter. The littler the children are, the more enormous the stage seems, lending the tale enchantment. Yes, there are memorable adult characters: the Sugarplum Fairy and Dewdrop, Mother Ginger and the Mouse King. But the kids are the ballet’s heart, the glue — what guides us down that path to feel the feelings.

This year, rejoice! The tiny bodies are back — though, because of the pandemic, they have little experience. Of the 126 in the production (there are two casts) 108 are first-timers in the show.

Dena Abergel, City Ballet’s children’s repertory director, sees “The Nutcracker,” which opens Friday at Lincoln Center, as Balanchine’s training ground: It teaches children of the City Ballet-affiliated school how to become performers.

This is a festive NYT holiday article by Gia Kourlas. It is filled with colorful videos and still photos of the children, taken by Erik Tanner. I highly recommend reading the entire article, which you can do even if you do not subscribe to the Times, because the link above in the title is a “gift link” that allows readers access to the article. Enjoy!

[edited]

______________

The gifs above are edited versions of Erik Tanner’s videos/photo; the captions (with formatting edits) are from the article.

#the nutcracker#school of the american ballet#george balanchine#new york city ballet#lincoln center#child ballet performers#gia kourlas#erik tanner#the new york times#my gifs#my edits

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Favorite ABT dancers?

So…this is tricky because there aren't a lot of bootleg videos of performances online to gauge current dancers. Recently, I've only seen Cate "Hurricane" Hurlin live — and her nickname absolutely lives up to the hype. Hurlin is very, very special — an incredible talent. Same with Aran Bell.

I saw Sarah Lane after she was canned from ABT and I was very impressed. Gillian Murphy is probably their best Odile / Odette in a generation. Years ago, I saw Julie Kent in Juliet…absolute perfection. But they are part of the old guard…. But I think there's an exciting rooster of new dancers catching fire there - Chloe Misseldine, Jake Roxander, Devon Teusch. And I'm excited to see where Susan Jaffe's leadership takes the company. Unlike MacKenzie who relied on bringing big-name international stars, I hope Jaffe develops and promotes internal talent. It creates a healthier working environment. I'm going to try to catch a few performances this fall, but lately I've been relying on Gia Kourlas' reviews in The New York Times and Marina Harss writings in Fjord Review — both have subscription firewalls. Sorry…that's a long response to say "the jury's out" but I'm excited for ABT for the first time in a long time. BTW, Julie Kent is leaving DC and will be co-director of the Houston Ballet. I'm very exited to see what she does for the company.

#ballet#ABT#American Ballet Theater#Cate Hurlin#Aran Bell#Sarah Lane#Gillian Murphy#Julie Kent is a queen#Gillian Murphy is a goddess

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antonio Velardo shares: Review: A Japanese ‘Boléro’? It’s a Spooky Ride of Revenge. by Gia Kourlas

By Gia Kourlas At Japan Society, “Nihon Buyo in the 21st Century,” a rare showcase in New York of this style of Japanese dance, forges a link between the past and present. Published: January 25, 2024 at 12:18PM from NYT Arts https://ift.tt/QvzhCif via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

International SEO news: Review: In Like Water for Chocolate Plot Overtakes Ballet

By Gia Kourlas American Ballet Theater opened its summer season with Christopher Wheeldon’s new three-act ballet, inspired by a novel and film. Published: June 23, 2023 at 08:12PM from NYT Arts https://ift.tt/UReS2H0 via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

"A Surprising Stage for Dance: The Subway Platform" by Gia Kourlas and Angelo Silvio Vasta For The New York Times via NYT Arts https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/30/arts/dance/subway-dancing.html?partner=IFTTT

0 notes

Text

A Surprising Stage for Dance: The Subway Platform

By Gia Kourlas and Angelo Silvio Vasta For The New York Times The tap dancer Ja’Bowen brings his art underground, where kids learn steps, commuters dance along and his energizing performances are bursts of joy. Published: May 30, 2023 at 08:00AM from NYT Arts https://ift.tt/e81HJv3

0 notes

Text

‘A Quick 5’ and More with Pulitzer Prize-Winning Critic and Former Washington Post Dance Writer, Sarah Kaufman

And then there was one. In 2015, The Atlantic published an article called “The Death Of The American Dance Critic.” It lamented the fact that, with Gia Kourlas’ departure from Time Out New York, we were down to two full time critics covering dance for major news organizations in the United States: Alastair Macaulay at […] See original article at: https://mdtheatreguide.com/2023/03/a-quick-5-and-more-with-pulitzer-prize-winning-critic-and-former-washington-post-dance-writer-sarah-kaufman/

0 notes

Photo

Gia Kourlas, How We Use Our Bodies to Navigate a Pandemic Zadie Smith, “Dance Lessons for Writers,” in: Feel Free: Essays Anne Boyer, this virus

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

gabriella_guillaume_art:

#quotes @giadk #icedance #art #beauty #papadakiscizeron #gabriellapapadakis #guillaumecizeron @gabriellapapadakis @guillaume_cizeron

#moonlightsonata #icedance #freedance #art #beauty #papadakiscizeron #gabriellapapadakis #guillaumecizeron #Gadbois @gabriellapapadakis @guillaume_cizeron

#quotes @charlieawhite #icedance #art #beauty #papadakiscizeron #gabriellapapadakis #guillaumecizeron #Gadbois

(10.12.2018)

#gabriella papadakis#guillaume cizeron#papadakis cizeron#papadakis/cizeron#posts#both#charlie white#gia kourlas#gabriella_guillaume_art#giak#charlieawhite#fabiennetourneur#fabienne tourneur

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyra Nichols Rehearses Robbins

from the New York Times, January 29, 2003

Easy Does It: Bringing Old-School Wisdom to City Ballet

Kyra Nichols, a former principal, returns to the company for the first time since her 2007 retirement to coach ballets by Balanchine and Robbins.

By Gia Kourlas Jan. 29, 2023

Indiana Woodward knew her time with Kyra Nichols was dwindling: It was the last hour they would spend together before Nichols, an esteemed former New York City Ballet principal, had to head back to her day job as a professor at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music.

For City Ballet’s winter season, Nichols had returned—for the first time since her 2007 retirement—to coach dancers in George Balanchine’s “Donizetti Variations” and “Walpurgisnacht,” as well as Jerome Robbins’s “Rondo,” an understated, little-seen ballet created for Nichols and Stephanie Saland in 1980.

A rehearsal for that ballet was about to begin, and Woodward and Nichols were talking—with the repertory director Christine Redpath—about energy: how to save it, how to store it, how to look better by doing less.

Woodward, with imploring eyes, turned to Nichols with a request: “Whenever you think of it, just send us a message”—she made a calming motion by patting down the air with her hands—“saying, ‘Take it easy.’”

Easy, of course, isn’t always so easy. But the idea behind it is important: How can a dancer replace force with something more free? How can she explore the possibilities of effortless dancing, the kind that Nichols was known for? She knew how to be natural. Throughout her 33-year career with City Ballet, Nichols made it seem as if steps were flowing—sometimes gently, sometimes with a wild, gushing power—through her limbs, her torso, her elegant upper body, as epitomized in the dynamic épaulement of her shoulders and head.

Nichols’s dancing was expansive and free, yet in the service of the choreography—or, really, the musicality within the choreography. It’s not so different from the way she demonstrates movement in the studio: She moves.

Above: Nichols, left, with Christine Redpath, a City Ballet repertory director. It was Redpath who asked Nichols for help when she began putting “Rondo” together. Photo: Nina Westervelt for The New York Times

The invitation to coach was a happy surprise. “I thought, the time will come if they want me to come,” she said. “I didn’t push it. Hopefully, I’ll come back. It’s been a really great experience.” It started when Redpath began putting together “Rondo,” and asked Nichols for help. Enlisting former company members from the Balanchine era to coach dancers from the current generation is something that City Ballet, under its artistic director, Jonathan Stafford, and associate artistic director, Wendy Whelan, has continued to implement. Mikhail Baryshnikov, Edward Villella, Patricia McBride and Suzanne Farrell have all come back to coach; this season, Adam Luders returned along with Nichols.

Beginning Tuesday, “Rondo” will take the stage again, featuring the pairing of Mira Nadon and Isabella LaFreniere—and, later, Woodward and Olivia MacKinnon. (LaFreniere and MacKinnon perform Nichols’s role.) “He would have Stephanie do something that was simple,” Nichols said of Robbins. “And then he had me do a version that was just a little bit harder.”

“Rondo” didn’t last beyond 1980 at City Ballet. Yet the pas de deux, set to Mozart’s Rondo in A minor for solo piano, has a gleaming simplicity and an unsentimental feeling of sisterhood. At the time of its premiere, Robbins wrote to Leonard Bernstein, inviting him to see the ballet: “I like it,” Robbins said, “although like the music, it is a fairly quiet work.”

Quiet or not, Nichols feels that “anything of Jerry’s should just always be kept—and Balanchine,” she said. “Even if it wasn’t a big success, it still has so much in it. It’s important to the dancers, this new generation.”

Robbins began creating “Rondo” with little fanfare, beginning, as he often did, by playing around in the studio. “He got us in there and was just toying with different ideas and then, all of a sudden,” Nichols said, “they wanted it on opening night that season.”

Above: Kyra Nichols, right, coaching Isabella LaFreniere, left, and Mira Nadon in Jerome Robbins’s “Rondo.” Photo: Nina Westervelt for The New York Times

Robbins labored over his ballets. When he learned that “Rondo” would be performed so soon, he secured the only stage rehearsal possible: one hour on the day before the premiere while the stagehands were on their dinner break.

“They were loading in,” Nichols said. “There was no floor laid. The wings were up, and they were putting all the lights in. So when they went to dinner, we ran ‘Rondo.’ We didn’t wear pointe shoes, but he could see, visually, what we were dancing.”

In the ballet, the two women echo each other closely, performing in sync or in canon as one trails behind the other in light runs and jumps, tightly knitted chaîné turns—in which alternating feet spin across the floor like a chain—and tiny steps that send them floating across the stage. They partner each other, too: “Rondo” is a crystalline display of two women dancing together, working together, as Nichols put it, to make it work.

“It was more your body doing it, especially with Jerry,” she said. “Look at the other girl, but don’t make love to her.”

In a rehearsal with Nadon and LaFreniere, Nichols urged the dancers not only to be easy, but also to be natural—a hallmark of Robbins’s choreography. “You have a beautiful pointed toe,” she said. “Just step on it.”

“Rondo” looks serene, but is it? “This is a beast, this is so hard; how did she make this look so easy?” LaFreniere said, referring to Nichols, in a video interview with Nadon. “One of the first things she said when she came into the studio was like, ‘Just less, everything less.’ After one of our run-throughs of ‘Rondo,’ I was super, super sweaty. And she looked at us and she said, ‘Yeah, we’re going to have to learn how to breathe.’”

Nadon added: “I think as dancers, our tendency is to want to work really hard because we want to push our physicality. And sometimes the hardest thing is to do a little less and to be a little calmer and to let the movement speak for itself.”

That’s part of what Nichols grasped while working with Robbins: not being balletic about movement quality. Walking, standing—everyday movements performed by dancers without affectation to create something new, a kind of pedestrian classicism. “I didn’t have it right off the bat either,” Nichols said. “How many times did I walk across the stage looking at the lights in ‘Dances at a Gathering’ and him going, ‘No, let’s do it again.’ Not walking on the music, being casual, not pointing the toe—it’s so different than taking ballet class.”

Nichols says she loves coaching, loves to share what she learned; during her time at City Ballet, she was especially flattered to be asked to teach a variations class at the company-affiliated School of American Ballet. She focused on “Spring” in Robbins’s “The Four Seasons.” She taught it the way Robbins originally choreographed it—with turns to the left and right. Now, turns are generally performed to the right; most dancers are right turners. For Nichols, that distorts the structure of the variation, how its choreography fills the stage. She recalled the first time she was in the studio with Robbins; up to that point, in “Goldberg Variations” and “Fanfare,” two of his ballets, she found herself positioned in the back row. She assumed she wasn’t going to become a Robbins dancer and, as she told herself, that was OK: She was working with Balanchine. But then, to her surprise, she was called to a rehearsal with Robbins.

“He was still dancing around a lot at that point,” she said. “I got there, and he started moving. He moved to the left. He did hops on my weak foot.”

She was honored to be in the room. She wanted to please him, so she followed along. “And what was I supposed to say? ‘Um, Mr. Robbins, that’s my weak side. I can’t turn to that side.’ I was 19 at that point. I was like, I’m in the room with Jerry Robbins. I just did it.”

Photo: Nina Westerveldt for the NY Times

#Kyra Nichols#Jerome Robbins#New York City Ballet#NYCB#Christine Redpath#Isabella LaFreniere#Mira Nadon#Indiana Woodward#Gia Kourlas#Nina Westerveldt#ballet#rehearsal#Balanchine dancer

0 notes

Link

By BY GIA KOURLAS from Arts in the New York Times-https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/16/arts/dance/in-the-heights-dance.html?partner=IFTTT The movie’s choreographic team, led by Christopher Scott, gets raw and real with dancers — so many! — who give in to thrilling perpetual motion. ‘In the Heights,’ Where the Streets Explode With Dance New York Times

0 notes

Link

By Gia Kourlas

Published Jan. 22, 2021Updated Jan. 23, 2021

Bruce Lee talked about emptying the mind in order to become formless and shapeless like water, which “can flow or it can crash,” he said. “Be water, my friend.”

The pandemic has made us shift our perspectives in so many ways, but Lee’s guidance rings true: We need to be water. And we need to move. It heals. And if more people moved, they might just find their way to dance.

Dancers know that how you are in your body relates to how you are in your mind and how you move through the world. Most New Yorkers live in cramped quarters that now often double as workplaces, too. Our bodies are constricted. And though we aren’t back to a complete shutdown the way we were in March, as the pandemic drags on, it’s getting harder and harder to find moments of release and wonder.

Winter is not my greatest season. I mean it can be a struggle to stand. But when I least feel like moving is when I need it the most. It’s good to sweat. I run. Last spring, a friend who knows me well recommended a trainer, Erika Hearn, and she has saved my body and mind through her Instagram classes, which mix strength, Powerstrike kickboxing, resistance band-work and mobility. It’s a meticulous total package; plus, she moves with such dynamic ease that watching and mirroring her fluid execution of steps — including her occasional human moments of imperfection — in some small way fills the gap of not being able to see live dance. When she says “stay with me” it’s not only about completing a movement, it’s about having faith in movement.

Still, it’s hard to remain optimistic about much of anything at dusk. It’s too cold to roam the city; we’re basically stuck inside. But even our milder version of lockdown doesn’t have to feel as if we’re locked up. We can use movement as a way to look inward. Through stillness and slowing down, we can create a rich sense of space by moving our minds around our bodies. Slowing down can feel like freedom — and, for me, that’s a good antidote to dusk.

Somatic practice — named for “soma” or the living body — is a way to connect the mind and body that encourages internal attentiveness. “We’re talking about allowing the living body to inform behavior,” Martha Eddy, an esteemed somatic movement therapist, said. “But then how do you do that? It’s by using your proprioception” — the ability to feel the body in space — “and your kinesthetic awareness.”

Focusing on the navigation of space and becoming conscious of how you move, especially when outdoor ventures are limited, is unsettling and grounding, excruciating and exciting, but always transformative. It’s a trip you can take. “It’s a mind journey,” Eddy said. “And it’s a mind journey that’s real.”

During the pandemic, virtual training has opened up the somatic approach to the bigger world. Classes in the Feldenkrais Method and BodyMind Dancing are available at Movement Research at no cost. (The joke is that they’re priceless.) Eddy’s BodyMind Dancing, appropriate for any level or any body, is a delightful, curative way to spend a Monday night.

It’s fitting that a key somatic principle, Eddy said, is the idea of slowing down. “I call it slowing down to feel,” she said. “Related to that is going into the breath, and related to that is releasing tension. Sometimes I separate those two and sometimes I keep them together: releasing tension and breathing.”

There are levels, but slowing down to feel isn’t a static act: It’s about shifting to a more internal place. The hope is that you emerge from a somatic class and bring some of that awareness into your everyday life. I know I have. In a time when it seems we have little control, having agency over our bodies — and our internal world — is a kind of power. By engaging in a somatic experience, you come to realize that these practices are not just about creating flexible bodies, but flexible minds.

The Feldenkrais Method, created by Moshe Feldenkrais, does that and more with its system of exercises that zone in on skeletal function and self-awareness through movement. It’s slow, methodical and controlled. Sometimes the movements seem imperceptible. You are told to hold back, and you are also on your back a good deal. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

Rebecca Davis, a Feldenkrais practitioner, broke it down: “You do a movement and you pay attention to how it feels,” she said. “You do something with the right side. You do that same action on the left side. I’ve tried to distill it to that I teach people how to pay attention, what to pay attention to and why it matters.”

In one class I took focusing on the feet and legs, Davis told us — repeatedly — to stay in a 5 percent zone of range and effort. This, it turned out, was impossible. It’s like my muscles were laughing at me. Attempting to do less is a hard, humbling act.

“When I say, ‘Now slowly tilt your legs to the right,’ what comes out of people is definitely not my idea of slow,” Davis said later. “We have to recalibrate pacing, timing because for this work in particular it’s the sensory details that we’re interested in. Once you slow down and start paying attention to yourself in a different way, that’s really where change can happen.”

Davis, who teaches at Movement Research (her next classes are in February) and has an online program, talks you through the physical instructions, which in turn develops a skill: You listen both to a voice and to your body. While executing small, detailed movements, she invites the release of the eyes, the jaw, the forehead — sites of parasitic effort, where parts of the body don’t need to work. It’s a way to quiet ourselves so the sensory details of our experience become clearer. It’s like relearning yourself from the inside out, and the breakthroughs are otherworldly.

“When your weight is not collapsing onto your spine, onto your skeleton — when you’re not falling onto yourself, when you figure out how to use your feet so that your weight is coming up and through, that feels so good,” Davis said. “You’re lighter. It takes less work to move.”

But it also takes work to remain still. Early in the pandemic, I found yin yoga, a practice focusing on passive poses, and Kassandra Reinhardt, who has been teaching on YouTube since 2014. She can ease the memory of any miserable day, and so can yin, which isn’t about stretching muscles, but relaxing into them in order to release ligaments, joints, bones and fascia. Poses are held for at least two minutes and usually longer.

Some of them feel good; others feel like death. “We’re slowly breaking down physical tension that we might have been carrying for years,” she said. “Maybe you just have it from the run that you did earlier that day, but maybe this is decades worth of tightness and tension that you’re now consciously releasing.”

It’s a process: You find your pose — and your edge within it — and breathe while remaining still. If all goes well, you melt lower and deeper; when class is over, it’s like you’ve shed a layer of skin.

Embracing stillness-oriented practices is important to Marie Janicek, a dancer turned personal trainer who hosts a podcast, “This Thing Called Movement,” that explores how movement impacts our lives. “It allows us to flesh out the true depth and subtlety and dimensionality that’s inherent in the movements we do day to day,” she said. “And then we have a greater ability to appreciate all the threads of what’s happening in our bodies, in our minds, in our sense of self. Not just when we’re actually moving, but then outside of that as well.”

As Eddy pointed out, even when we are seemingly still, there are physiological rhythms that occur in our bodies. “Which is our breath, which is our blood flow, which is our craniosacral rhythm, which is the cerebrospinal fluid around the nervous system,” she said.

For her, it’s an orchestra. “Sometimes it’s very, very quiet and sometimes one particular instrument is very dominant,” she said. “But no part disappears.”

You can access that dimension and richness in her classes, too. In a recent BodyMind Dancing session, we were swinging and swaying in whatever way we chose. She said, “Let the weight move into lightness.”

It was the sensation of moving heavy water — thick yet unbound — and suddenly being swept to shore by a wave. In my apartment. After class ended, Eddy asked if anyone wanted to share their experience. One woman, effusive and out of breath, popped onto my screen and said she had been working up until the time class started, but was determined to take it anyway. She went to a park. But she didn’t want to lie on the ground to perform the exercises.

“I found a tree!” she said.

Movement can do all sorts of things. On this night it brought the world a little closer together. “Thanks,” Eddy said, “for bringing the tree to us.”

#feldenkrais method#exercise#articles#Body Alive#Structural integration Atlanta#alexander technique#movement#awareness#kinesthesia

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In 2011, he did finally publish a memoir: “I Was a Dancer.” It is worth a thorough read with Post-it notes; afterward, keep it nearby to dip into when life feels too ordinary. His love for all things dance was enhanced by his profound curiosity for the world around him. And, no surprise, the book is about more than just himself; it’s about the world that he inhabited. In one moment, he watches the ballerina Suzanne Farrell from the wings and wonders: “Who’s in there transforming her? Certain dancers become larger than just a dancer doing a role; they seem to channel a greater force. Suzanne danced possessed, as if inhabited by a goddess of dance who was using her as a vent.”--Gia Kourlas, "Jacques d'Amboise, a Ballet Star Who Believed in Dance for All, New York Times

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antonio Velardo shares: In a Land of Primary Colors, Home Is Where the Bounce House Is by Gia Kourlas

By Gia Kourlas As part of Under the Radar, Nile Harris resurrects his play that weaves together text, sound, minstrelsy and dance to explore the American experience. Published: January 5, 2024 at 10:00AM from NYT Arts https://ift.tt/oXKFmaP via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

A Review of Balanchine’s “Valse Fantasie” (performed by the American Ballet Theatre)

Preface: A few years ago I wrote a performance review piece after watching American Ballet Theatre’s Valse Fantaisie . I never published it on here but I stumbled upon it today and thought that I should share. After all, it may let us all imagine ourselves at the ballet or theatre...maybe even the opera. Something that may not happen again in a very long time. So...hope you enjoy.

On October 24th, I had the privilege of watching George Balanchine’s Valse Fantaisie performed by American Ballet Theatre. Valse Fantaisie, which translates to “Fantasy Waltz”, is a mystical performance of six dancers moving to a rhythmic and joyful piece of music by Mikhail Glinka. Balanchine’s neoclassical elements are quite visible in the choreography - With no story-line to fall on, the performance relied primarily on the visual and auditory allurement of the audience. From the stunning costumes, to the lively music, and the shapes and geometry that were created on stage, Balanchine (through ABT of course) was able to successfully hook his audience. Balanchine himself has stated that “A ballet may contain a story, but the visual spectacle, not the story, is the essential element. The music of great musicians, it can be enjoyed and understood without any verbal introduction and the choreographer and the dancer must remember that they reach the audience through the eye and the audience, in its turn, must train itself to see what is performed upon the stage.” [2]

The music, made up of quick and delicate melodies in B minor, goes by the ballet’s same name and was composed by Mikhail Glinka who is Russia’s first national composer and considered to be the country’s Mozart. [1] A live orchestra made the music come alive and its echo effect (string instruments playing first and then flutes echoing the same melody after) created a hypnotizing sensation which made the performance extremely bewitching for the audience. The costumes were of course a vital cause of this enchanting atmosphere as well. They were mystical and fairy like: The five female dancers wore blue-green tutus whilst the male dancer wore a white bodysuit with blue embellishments.

Balanchine’s neoclassical elements are clearly evident in his choreography. The piece is stripped of detail and elaborate staging: “As a choreographer, Balanchine has generally tended to de-emphasize plot in his ballets, preferring to let ‘dance be the star of the show’”.[2] There is no story line and the focus is completely on the music, the dancers, and their effortless technique. Gia Kourlas from the New York Times states that the the way in which the dancers move is what contributes to the airy feel: “Balanchine’s windswept, rapturous “Valse Fantaisie,” one man, James Whiteside, and five women, with Hee Seo in the lead, twist and turn to Glinka’s music as if their bodies were controlled by the air. It’s over before you know it: After four women exit, the leads leap into opposite wings”.

Male lead, James Whiteside, displayed extreme athleticism and precision. Before joining American Ballet Theatre in 2012, Whiteside danced with Boston Ballet under instruction of director Raymond Lukens.[4] Female lead, Hee Seo, was trained in South Korea before joining American Ballet Theatre in 2004.[5] The corps consisted of Lauren Post, Melanie Hamrick, Paulina Waski, and Brittany De Grofft. Balanchine purposely chose four female corps de ballet members to dance without male partners in order to create his ideal choreographic structure on stage: “Balanchine offers a highly distilled treatment of one of his perennial themes… a solitary male has not one but several women to choose from. Another choreographer might have paired off the other women with partners, but Balanchine catches us off balance here. The man dances with a ballerina but he also dances in a frame of four other women. They are a miniature corps and an amplification of an ideal female. At the end, there is no lasting encounter. Everything vanishes - the soloists are swept off stage and the two principals leap out in opposite directions.”[6]

There were a variety of different choreographic structures present throughout the nine minute long piece. Valse Fantaisie, being that it is a waltz performance, involved steps done in triple time such as pas de valses, ballancés, and a few series of pas de bourrées. Although the choreography was neoclassical, there were still many similar elements to the classical Cecchetti technique that I trained in. Because there were four female dancers part of the corps de ballet, and two lead dancers (one male and one female), there were a lot of circular pathways constructed by the corps which existed to highlight the two principal dancers. There were also many frequent exits and entrances: Sometimes, only the corps would be present on stage (usually performing a pas de quatre) and whenever the music would crescendo, the two principles dancers would appear and the corps dancers would exit leaving the principal dancers to perform a romantic pas de deux. And when all the dancers were present on stage, it usually involved the corps standing in a circle performing balancés around the principal dancers who were executing something more technically complex. For example, at one point in the performance, the corps executed balancés in a circular pathway around the lead dancers. While the corps were performing these balancés, the lead dancers did piqué arabesques across the floor. Sometimes, the corps would also dance behind the principal dancers and mimic the very same movements.

Although the ballet seems to have received mostly positive responses so far, there have been critiques made in terms of the casting. Kourlas for example, believes that Whiteside and Seo did not fully meet the demands of the piece: “Valse Fantaisie is a tale of speed and drive; Mr. Whiteside handled Ms. Seo admirably, but was given to stiffness in his solos, and Ms. Seo, in blue, started strong and faded in momentum”. [3] Perhaps, this is because American Ballet Theatre rarely does works by Balanchine and so the dancers may not be as accustomed to the Balanchine method. It is also, just the very beginning of the season. Overall, I think the performance was outstanding: The costumes, the music, the choreography all perfectly synced together and created a very fantastical feel.

To watch a 1973 version of the dance, click here.

1 "New York City Ballet - Home." NYCB. N.p., n.d. Web. 5 Nov. 2015. from http://www.nycballet.com/ballets/p/pas-de-trois-(glinka).aspx 2 George Balanchine - ABT. (n.d.). Retrieved October 28, 2015, from http://www.abt.org/education/archive/choreographers/balanchine_g.html 3 Kourlas, G. (2015, October 25). Review: Choreography Is the Star at American Ballet Theater. Retrieved October 28, 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/26/arts/dance/review-choreography-is-the-star-at-american-bal let-theater.html?_r=0 4 "AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE: JAMES WHITESIDE." AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE: JAMES WHITESIDE. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Nov. 2015. http://www.abt.org/dancers/dancer_display.asp?Dancer_ID=300 5 "AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE: Hee Seo." AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE: Hee Seo. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Nov. 2015. http://www.abt.org/dancers/detail.asp?Dancer_ID=155 6 Kisselgoff, Anna. "BALLET: 'VALSE-FANTAISIE'" The New York Times. The New York Times, 30 Apr. 1985. Web. 8 Nov. 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/1985/05/01/arts/ballet-valse-fantaisie.html Photos: Courtesy of Marty Sohl

#balanchine#ballet#american ballet theatre#performance#theatre#dance#dancer#performance review#ballerina#new york

2 notes

·

View notes